Bookshop.org, which shares profits with local retailers, is now offering Adventures in the Teaching Trade and copies of my other books. Buyers will find some books at lower prices than available on other outlets.

Book News

Apple Books recently announced the eBook edition of Adventures in the Teaching Trade is now available to order from the United States, Canada, Spain, the UK and New Zealand. Residents of those countries are now free to go nuts. Autographed hard copies are available at bryanjoneswriter.com to residents of anywhere.

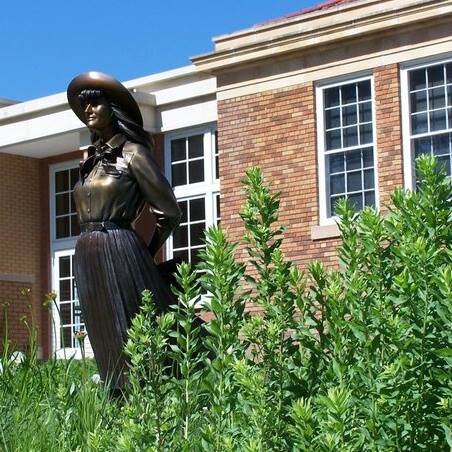

Mari Sandoz High Plains Heritage Center

On September 25th, the Mari Sandoz Western Heritage Center at Chadron State College hosted a North of the Platte, South of the Niobrara book talk/signing. My keen interest in the life and writings of Mari Sandoz goes back over 60 years, since my time in junior high school and making an appearance at the Sandoz Center has long been a personal dream. As it turned out, the actuality far exceeded the anticipation. The event was well-attended, thanks to Director Laure Sinn and her crack staff’s publicity efforts, which were as creative as they were thorough, employing social media, print ads and radio interviews.

The audience shared memorable personal stories, including several Sandoz family anecdotes, and we signed a fair number of books. Two sisters-in-law, who make a habit of attending book signings and then hiding their loot from their husbands, bought one of every book on offer. We hope they show up at our next book event.

Recent Appearances

Prior to the Broken Bow Library appearance, David Birnie of KBBN radio conducted a wide-ranging interview.

Tuesday afternoon Bob Brogan of KRVN radio aired segments from an interview we taped on Monday.

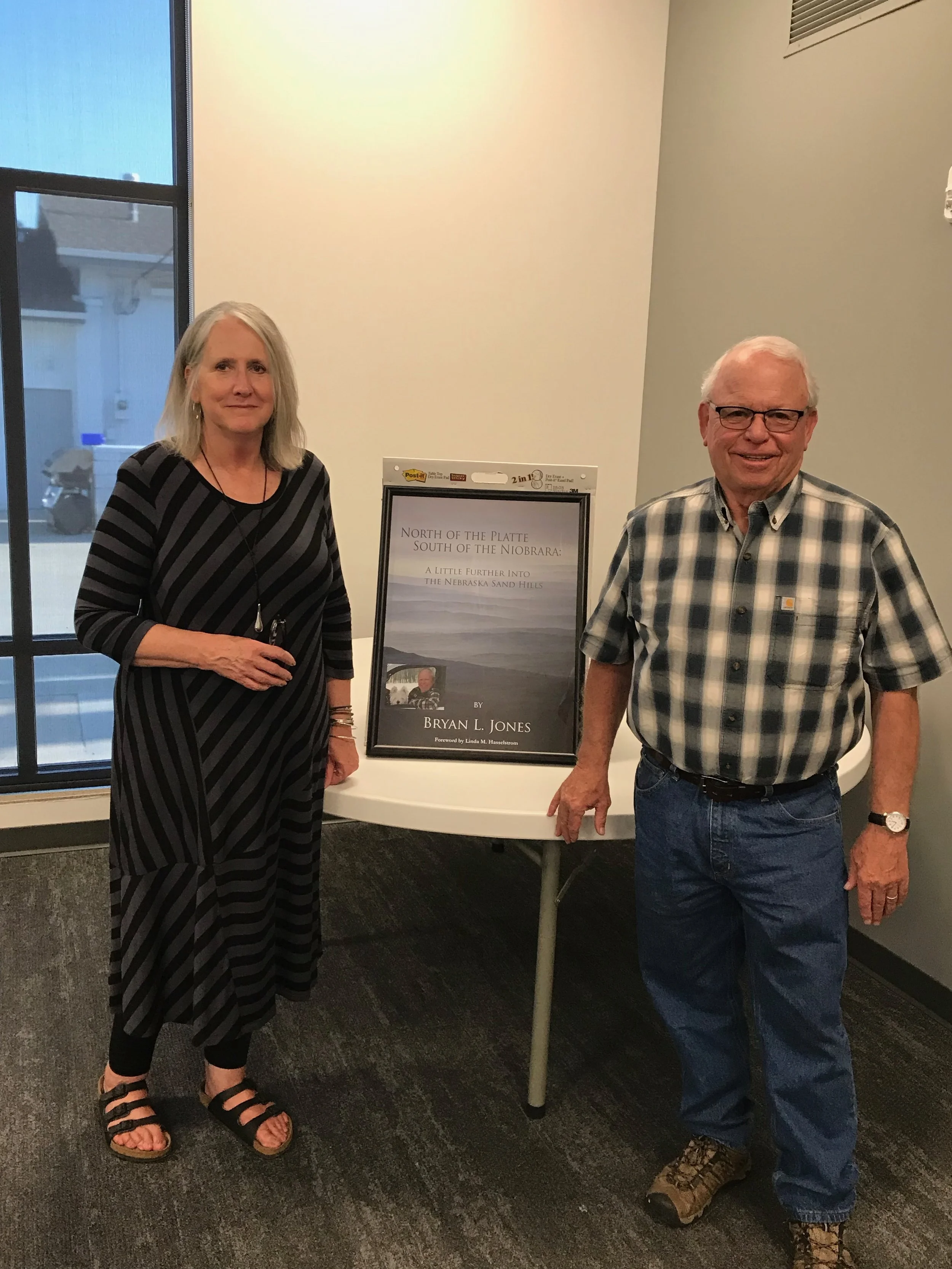

Kearney Public Library

Christy Walsh and the Kearney Public Library hosted a book talk/signing Tuesday evening. Extensive advance publicity contributed to a good crowd, forcing Christy to add seating capacity several times. Active audience participation made for a lively evening. We were happy to see several old friends in the audience, including Marcia Welch and Pat Hoehner, and were able to make new friends. Christy anticipated all our requirements, making doubly and triply sure everything went smoothly.

Wednesday morning Carol Staab hosted us on NTV’s award winning Good Life talk show. Although she was bitterly disappointed we didn’t bring Finlay, she recovered sufficiently to ask pertinent questions and fill in dead air space as it occurred.

Broken Bow Public Library

Joan Birnie and the Broken Bow Public Library hosted a book/talk signing Wednesday evening. The audience proved even more inquisitive than the Kearney audience and we heard many new stories. Joan is a peach and could not have been a more welcoming or attentive host.

Both the Kearney and Broken Bow libraries have requested return engagements. We are grateful.

June Appearances

Cythia Miller hosted a book talk/signing at The Most Unlikely Place (art gallery, coffee house, cafe, event center) in Lewellen, Nebraska, at noon on Friday, June 28th. We spoke to a full house and enjoyed meeting local artist/photographer Bob Brummett in person after engaging in an extensive email correspondence for the past couple of years.

Vicki Retzlaff of the Grant County Library and Ginger Fouse of the Grant County Museum hosted a book signing on Saturday, June 29th at the Grant County Courthouse in Hyannis, Nebraska. We met several ranchers who already owned the book, but were purchasing copies for others, and heard memorable Sand Hills stories. Later we attended our first Ranch Rodeo at the Grant County Fair Grounds.

Nicole Hoffman and the Mullen Arts Center hosted a book talk/signing in Mullen, Nebraska, on the afternoon of Sunday, June 30th. Nicole organized the event and rounded up an attentive audience. We were able to visit with a former employee of Judge Moursund when he leased the McMurtrey Ranch and the caretaker of Herman the Prairie Chicken, famous for his skills at sorting cattle and riding ATVs.

Book Talk/Signing at the West Nebraska Family Research and History Center in Scottsbluff, Nebraska

On February 10th the West Nebraska Family Research & History Center in Scottbluff provided the venue for a book talk/signing. Floyd Smith, III created the Center after he became interested in genealogy and began to amass a collection of local and county histories, obituaries from old newspapers and a staff of helpful volunteers who assist pilgrims searching for lost relatives. Floyd did a fine job publicizing the signing, which helped boost the crowd on a bitterly cold afternoon.

Allen and Ruth Vance served as gracious hosts and helped us set up for the signing and the book talk. Except for a punk newspaper reporter, Kathy and I were the youngest in attendance. Three couples had been married for over 60 years, giving us a worthy, if a bit lofty goal. We met Lucien Kicken, a shirtail relation of the Sandoz clan, who shared a story about Old Jules locating his family and scaring small children half to death in the process.

Anyone interested in family history would find a treasure of useful resources at the Center, including access to all the data bases so handy for in depth research.

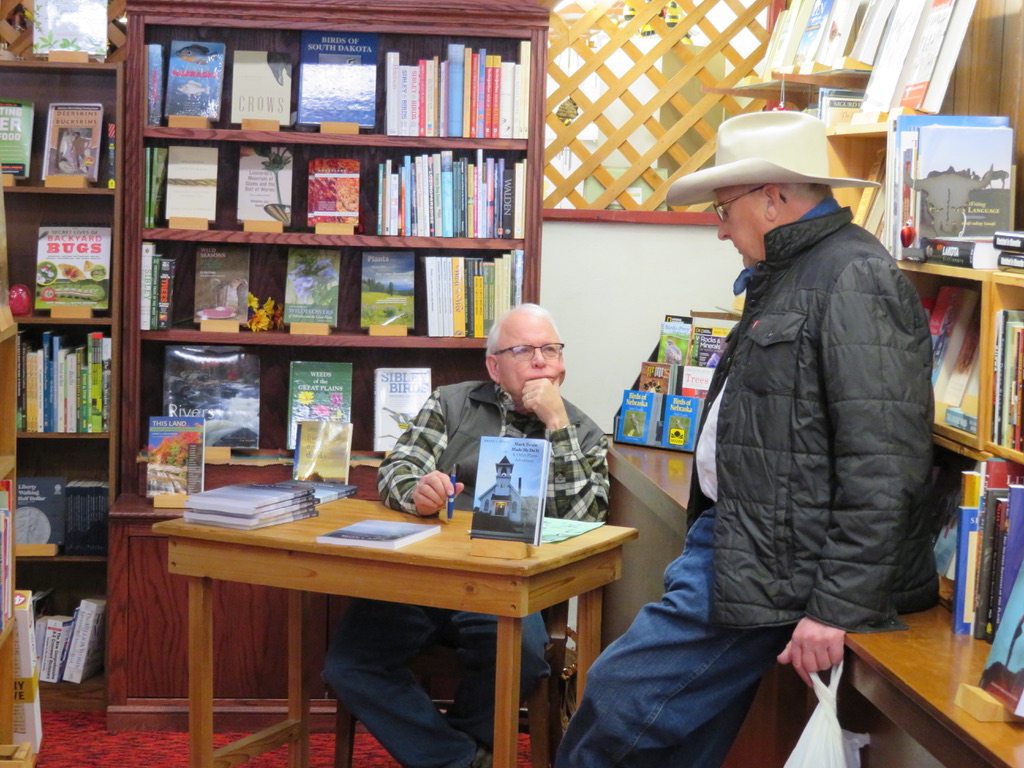

Book Signing at the Plains Trading Company in Valentine, Nebraska

On February 9th The Plains Trading Company Booksellers in Valentine hosted a book signing for North of the Platte. Duane and Darlene Gudgel, who own this iconic bookstore, heavily promoted the event with radio and print ads and provided attentive logistical support during the signing. We were able to renew friendships with some of the book subjects and visit with Sand Hill residents who had their own rich stories to share. The event took place during the annual Bull Bash weekend in Valentine, when pens of bulls occupy the center of Main Street. A crowd of hardy bull buyers shopped the offerings in spite of the frigid weather.

A note on The Plains Trading Company Booksellers:

The Plains Trading Company houses a lovingly selected collection any bibliophile with a taste for the American West would be proud to own. We grabbed a rare Nellie Snyder Yost volume and a brand new copy of Charles Barron McIntosh’s masterpiece The Nebraska Sand Hills: The Human Landscape, which has been out of print for several years. Since the last time we visited, Duane and Darlene have added excellent coffee and an impressive array of Nebraska wines to the amenities. If you ever find yourself within two thousand miles of Valentine, Nebraska, waste no time making a bee line for The Plains Trading Company. You’ll not regret a second spent in this sanctuary of Western literature.

McCook Book Signing and News Account

I'd like to thank everyone who attended the book talk/book signing at the Museum of the High Plains in McCook on Saturday. We were able to visit with friends old and new. Along the way we collected a whole new set of Sand Hills stories. Special thanks to Connie Jo Discoe who performed all the set up and tear down and did such a terrific job with the publicity. Connie Jo even decorated the signing table with a large bowl of sand for the occasion!

Book News:

This week the McCook Gazette ran two stories on North of the Platte. Connie Jo Discoe, long time Gazette reporter, also covered the plane crash a few years back.

'North of the Platte' is author's third book

https://www.mccookgazette.com/story/2568352.html

Author inspired by cowboy ancestors, 'Old Jules'

https://www.mccookgazette.com/story/2568351.html